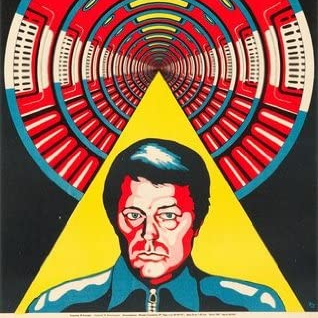

It’s been a little while since I watched Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris, the Soviet director’s 1973 movie adaptation of a classic sci-fi novel of the same name written by Stanislaw Lem. But the other day, it suddenly struck me that, for being a work from the Cold War, Solaris provides a metaphor that I have been grasping for—a metaphor that helps explain how large language models are able to learn and how they can generate information based on their learnings.

What could a semi-obscure Soviet film from 1973 have to tell us about AI? Let me explain. Be aware that there are spoilers ahead for the movie and if you haven’t seen it yet, it’s a masterpiece and well-worth a watch.

Also, a quick disclaimer: I am not an AI or machine learning engineer. This article is based on my current understanding of LLMs, which undoubtedly contains gaps and inaccuracies. That said, I am trying to instill in the reader an approximate conceptual framework for understanding LLMs rather than an exact description of how they function. We can then use this conceptual framework to try to probe the boundaries of what is possible using LLM-based AI.

LLMs and Solaris

The events of Solaris take place on a space station in orbit over the mysterious, eponymous planet Solaris, a planet covered by an enormous ocean. Kelvin, the story’s main character, arrives on the space station for a tour of duty and finds it almost abandoned. As he investigates this concerning state of affairs, he finds that the space station is haunted by incomprehensible creatures, sometimes taking the form of dwarfs, who run through a room and then disappear. These creatures appear to have little intelligence or agency.

Kelvin runs into an engineer on the space station who explains to him that the ocean on the planet Solaris is actually some kind of highly-advanced life-form. What appears to be an ocean is somehow a kind of liquid brain that surrounds the planet. And they have deduced that somehow, this oceanic brain is reading their brainwaves and, in response, generating the hobbled creatures on the spaceship. Why are the creatures deformed? It’s because the ocean can only imperfectly mimic patterns it finds in the humans’ brainwaves.

The ocean is not mimicking the astronaut’s brains—only the “output” of their brains. And so, only able to “train” itself on as many thoughts as the astronauts have had since arriving on Solaris, the copies it sends are very imperfect. Moreover, the astronauts theorize that the imperfections in its replicas must imply that the ocean does not have agency or understanding of the patterns it imitates. Instead, it’s a kind of passive defense mechanism evolved for unknown reasons. Is this starting to sound familiar?

An Alien Encyclopedia

I’d like to connect this back to large language models. Many people I’ve spoken with lately seem to have a view of AI as a kind of brain that, having been trained on all human knowledge, can use its vast powers of understanding to generate the answer to any question, data for any project, or wording for any article. Thinking of this way is a fundamental misunderstanding of AI. Large language models like ChatGPT do not “understand” anything.

To help us understand why, let’s try a thought experiment. Imagine you are given a vast encyclopedia about an alien planet that is written in an alien language. The encyclopedia has no pictures, so there is no way for you to see what an article might actually be about. At first, you might think that there is nothing you can learn from this encyclopedia. But then you realize that, while you can’t understand the language, you can see patterns in it.

The word “xwrs-xf” tends to be used nearby “bmdwp”. You start to develop a dictionary, “defining” alien words based on other words. You dictionary entry for “xwrs-xf” reads “62% of the time used near “bmdwp”. You notice when “mbg” is used next to “xwrs-xf”, the frequency of “bmdwp” jumps up to 86%. Repeating this process, as you painstakingly go through each word of each article and continue mapping words to their contexts, you begin to develop a sense for how sentences are constructed. You learn the pattern, although you don’t learn the meaning. Now, given some novel sentence, your dictionary, and a random number generator, you could mathematically try to predict what sentences might follow that initial sentence based on your context averages.

If you’ve done enough “training” with your dictionary, you can probably write a convincing sentence in that alien language. But fundamentally, you can never really know what you’re talking about because you’ve never actually seen the alien world. You have no lived experience with that world and without experience, there’s no way to connect to your words beyond a pretty positive likelihood that your sentence is “grammatically” correct.

Now, you’re given a second alien encyclopedia. Based on it, you’re able to adjust the contextual likelihoods written in your dictionary. You see some new usages for “xwrs-xf” and realize that in this text, when “mbg” is present, “bmdwp” is actually only used on average 44% of the time. You take the average of your new average and your old average, and update the dictionary to say “xwrs-xf” + “mbg” = “bmdwp” 65% of the time.

You can turn to any page and see the definition for an alien word, but its “definition” is always going to be in terms of another alien word. No matter how many new encyclopedias you use to fine-tune your dictionary, you won’t ever be able to actually know what you’re saying because the words will always be defined in terms of another word. After consuming enough alien books, your dictionary will become very good at telling you the contextual usage of an alien word. But fundamentally, to know what you’re talking about, you are missing something key—experience.

Epistemoligical Truth

As humans, we can learn abstract concepts like math, but we can also tie those concepts to our concrete experience of living in the world. You have a fundamental understanding of the word “two” that goes beyond the ways you’ve seen it used before. You know how to use the word “two” to construct a new idea, like “if I have one sock in my left hand and one sock in my right hand, I have two socks”. To a human, this is a concrete concept—one sock plus one sock equals two socks. To an LLM, this a fuzzy concept having to do with how many times it has seen the word “two” used with the word “one” and if it has seen that “sock” can be used with either of these words. An LLM has no way to experience the concept of “two” beyond the frequency and usages that have appeared in its dataset.

Without a way to experience the world or to learn concrete rules, an LLM won’t be able to say, invent a new concept, without breaking a concrete rule. Think about it—if you were to use your alien dictionary to construct a sentence without some experiential understanding of what the words meant, you’d very quickly say something wrong. An LLM trying to push boundaries might say “I walked on the water on the way to work”, trying to use “water” in a novel way. This is how hallucinations emerge.

Now, we know that this sentence is nonsense because you can’t walk on water—you’ve probably tried it before! But the only way an LLM can really know that it’s nonsense is if it has been given feedback that this is an incorrect usage of the word. This is how training can help to narrow the range of plausible word usages until eventually, the only usages that remain are those that approach reality. If we train the LLM not to use “water” in this novel way, we’re that much closer to it saying something else more plausible.

LLMs Are Fundamentally Bullshitters

This leads us to my main point: LLMs, as they currently stand, are fundamentally bullshitters. No matter how many parameters we scale them up to, no matter how much data they are trained on, no matter how fine-tuned they are on real conversations, they will never be able to go beyond bullshitting until they have a way to connect the words they learn to something fundamental.

This is true for the same reason that, no matter how many alien encyclopedias you translate into context frequencies in your alien dictionary, you will never be able to construct a sentence that describes something in the alien experience and know that what you are describing is real or logically consistent. It may be grammatically consistent, but that’s about the best you can hope for. You can never know what you’re talking about.

Asking an AI for a travel itinerary will never get you a meaningful, novel answer because an AI cannot experience travel. It can only ever get you some plausible combination of travel itinerary-adjacent words scoped to some domain that it has seen before. Sure, the final result may be a trip you could actually take, but only because someone wrote a similar trip down before and the AI consumed it.

Asking an AI for stock tips has the same problem. An AI does not know anything about the stock market, it’s just very good at using “stock market words” together in a way that is plausibly a valid sentence. Any meaning is tangential to whether the AI accomplished its function—generating a gramatically plausible sentence.

LLMs Are Probably Good At Abstraction

I think one corollary to this is that the more abstract a concept, the more likely an AI is to be able to “understand” the concept and use it correctly. Why? Because abstract concepts really are defined in terms of other words. It’s easier to be inventive and correct using the word “strange” than it is to use the word “mouth”. Strange can describe just about anything, while mouth refers to something very specific.

I think this is why AI is pretty good at programming. Programming is the art of writing abstract concepts in a simplified grammar. Not only that, but very few novel things are ever written in a programming language. There are many ways to implement a server, but there aren’t many novel ways to implement a server. So if an AI amalgamates a few different server implementations in a way that is plausible for the grammar it has learned, it will probably work. Or at least be pretty close.

Of course, the AI still won’t know what it is that it wrote :-)

Where To Next?

How do we get beyond this epistemological problem? I’m not sure. It seems like to move forward from here, AI will need a way of learning concrete rules and concepts—and maybe combining that with its frequency dictionary. For example, if you were to learn the English translation for just a few words in your alien dictionary, you could suddenly have a lot better chance of saying something epistemologically true in the alien language.

Maybe we need something like that, but for machines. Until then, feel free to buy into the hype a little bit—we’ve come a long way from GPT-3—but remember that no matter how many parameters we add, LLMs will still just be bullshit machines.

The ending of Solaris is quite beautiful. We cut from Kelvin trying to decide whether to leave the space station, to him suddenly in a field by a lake. He’s back in the village he grew up in. He sees the house he used to live in and approaches it. He looks in the window and stops.

His father, who died many years ago, is in the kitchen making food. It’s cloudy outside, but it’s raining in the house. Kelvin’s father looks up and sees him and they run to meet each other at the stoop by the front door. Kelvin kneels at his father’s feet, clutching him like the prodigal son returned.

As the camera zooms out, we see that all of this has taken place on an island in the ocean of Solaris. Solaris has created an imperfect copy of the world Kelvin wishes still existed, and Kelvin has decided to live in its mirage. Will we?

If you’d like to watch the ending of Solaris, see this video.